Holly Wantuck

Sap-Sucker: The Fuzzy Past and Even Fuzzier Future of Southwest Virginia’s Pine Bark Adelgid

One small, anonymous insect may soon draw the spotlight of the local stage.

The pine bark adelgid—a sap-sucking, tree-dwelling insect whose existence in southwest Virginia has been all but overlooked—may be a victim of population fluctuation and a pawn in predator complex reconstruction.

Holly Wantuch, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in Virginia Tech’s Department of Entomology, has been studying the natural history and predator complex of the pine bark adelgid with the hopes of understanding these potentially impending circumstances.

The pine bark adelgid’s main predators include tiny flies, lady bugs, and a particular beetle species formally known as Laricobius rubidus (“ruby beetle”). Recently, this East Coast native has been found crossbreeding with the Laricobius nigrinus (“black beetle”), a sibling species native to the Pacific Coast and imported for biocontrol of the hemlock woolly adelgid.

“The fact that the predators can produce reproductive offspring suggest that these species are very closely related,” said Scott Salom, a professor of forest entomology in the Department of Entomology at Virginia Tech and co-advisor of Wantuch. “Genetic analysis by others have confirmed this.”

Unlike its ruby-colored partner, the Laricobius nigrinus is not a significant predator of the pine bark adelgid and doesn’t really contribute to the overall predator complex. Given the differences in origin and diet, Wantuch’s study seeks to understand how the recent hybridization of these two beetle species may influence the predator complex.

The concern is whether or not this crossbreed is a harmless accident of nature or a potential domino effect of ecological reconstruction.

“Hybrids feed only on adelgids,” said Wantuch. “The threat of hybridization to rubidus populations comes from the fact that hybrids tend to show more nigrinus traits than rubidus—including choice of prey. They are more likely to feed on hemlock woolly adelgids than pine bark adelgids.”

Since hybrid beetles are fertile, and if they continue to crossbreed, then the population of pure ruby beetles may steadily decline. With fewer purebred ruby beetles to prey on the pine bark adelgid, and more hybrid beetles to choose to dine on other adelgid species, the pine bark adelgid population could be subject to population increase. However, whether or not this is an issue remains to be seen. It is an investigation that is ongoing and the main reason why Wantuch’s project was originally funded.

Prior to Wantuch’s study of the pine bark adelgid, previous research on the insect’s residence in southwest Virginia was all but missing. In fact, the limited amount of research that did exist was from a study that had been conducted way up north in Minnesota.

“We realized we knew very little about the PBA [pine bark adelgid] predator L. rubidus and so felt it was important to learn as much as we could about the predator and its natural prey” said Salom. “It turns out that the information on this system is quite limited and non-existent for the predator-prey’s southern geographic range.”

Since southwest Virginia is one of the southernmost points that the pine bark adelgid lives, Wantuch felt it necessary to study the insect and observe how variables in geographic location (i.e. topography, seasons, etc.) could affect its behavior. Thus, she began her research by systematically studying and observing the adelgid’s life cycle, or natural history. This includes everything from its birth and growth to reproduction and death.

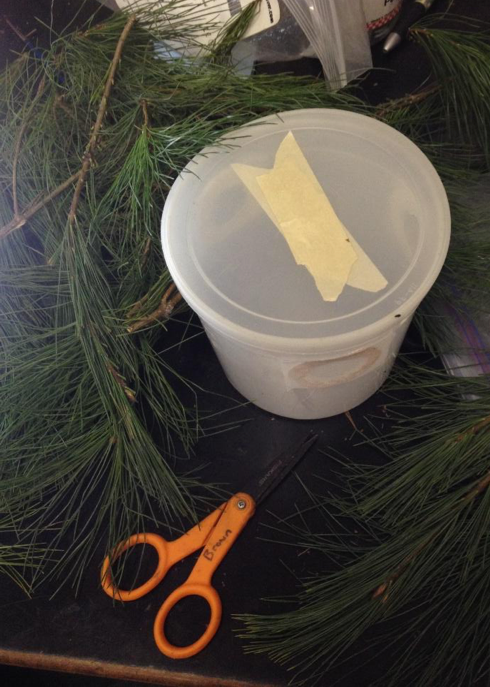

In order to study the adelgids and their predators, Wantuch took samples in the field for two years at three different sites. These sites included Pulaski County (Gatewood Reservoir), Wythe County (Mt. Rogers National Recreation Area), and Bland County (Jefferson National Forest). The adelgids were collected on pine branch clippings and tips. The predators were captured on beat sheets. These sheets resemble kites and collect the droppings from a shaken pine branch.

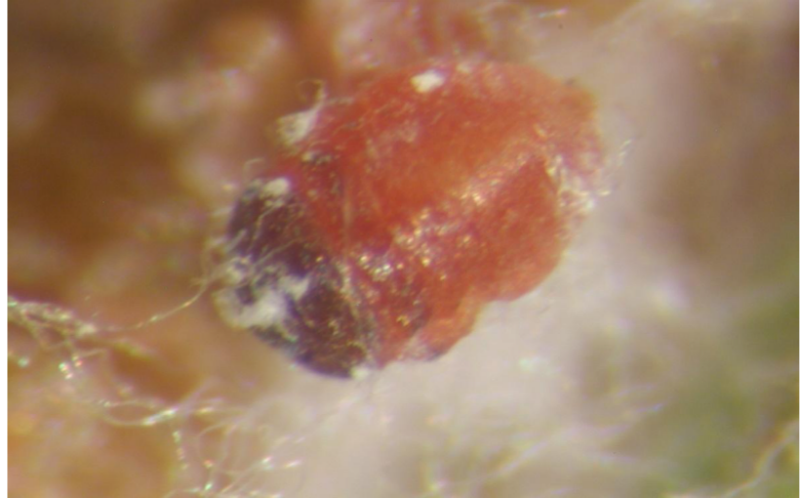

Back in the lab—which also doubles as her office and workplace—Wantuch would then store her specimens in refrigerated vials of ethanol. When the time came for observation, she would pour the vials into a Petri dish and view the specimens through a microscope. The small specks were suddenly transformed into enlarged monsters with long, thread-like mouths and shell-encased bodies! For months, hundreds of these specimens were measured (length, width, and head capsule width) and categorized by life stage.

From birth, all adelgids are female and thereby parthenogenetic, which means reproducing asexually. Upon hatching, the newborn pine bark adelgid will crawl around its birthplace for about three days before settling in the hook of a pine branch or some other protective location. As they are rather immobile creatures, this will most likely be their home for the remainder of their lives.

The adelgid has what is called a long “piercing/sucking” mouth part. Wantuch said that the construction and orientation of the mouth is just one of many ways that entomologists categorize bugs. This mouth part is typically longer than the insect itself. For instance, while the insect’s body may be 0.6mm long, its mouth may then be 1.7mm long!

They work their mouths into the trees and drink the sap (more formally known as the phloem), which is rich in nutrients from the photosynthesized needles of the tree. While such consumption by other adelgid species can harm the tree, the pine bark adelgid’s feeding does not seem to harm a healthy tree. Hair or wool is then secreted from their bodies and helps protect them from natural enemies. This also helps Wantuch easily identify the insect when searching in the field.

Wantuch has always had a love for insects and the outdoors, but it wasn’t until her last year as an undergraduate that she found her calling for entomology. As a pre-veterinary student enrolled in an entomology elective to fulfill core requirements, the class material prompted her previous love and understanding of bugs to quickly swarm back to her.

Wantuch studied apiculture in graduate school at North Carolina State University, and eventually started working with honeybees and integrated pest management (a multifaceted strategy for creating long-term pest control). For her excellent work, she received the North Carolina State Beekeepers Association John T. Ambrose Student Award in July 2009. During her time at Virginia Tech, she has presented her work on pine bark adelgid phenology and predators at various professional events such as the 2016 XXV International Congress of Entomology and the USDA Interagency Forum on Invasive Species.

“Much of this [work] would not have been known if it were not for Holly’s efforts. She is hard working, tenacious, and always upbeat, even in the face of adversity. It has been a pleasure to have her as part of our lab,” said Salom.

Whether or not the pine bark adelgid will be affected by this potential chain reaction of ecologic reconstruction remains to be seen. Wantuch will continue to observe the control and stability of the system. She even laughs and says that she almost feels like a villain for wanting the pine bark adelgid and/or hybrid beetle to have an outbreak, as this would fulfill her dissertation’s proposal and consequently make her one of the few “experts” who could find a way to fix the problem. However, such a future remains as fuzzy and unclear as the wool on a pine bark adelgid’s back.

Q&A: Meet Holly

Hometown

Granite Falls, NC

Academic Degrees

Animal Science (B.S.), North Carolina State University

Entomology (M.A.), North Carolina State University

Fralin Advisor

Dr. Scott Salom and Dr. Thomas Kuhar

What Attracted You to the Field?

I grew up in rural North Carolina as an only child, with no real neighbors. I spent most of my time outside, hanging out with our horses and dogs—and playing with insects. As an undergraduate at NC State, I happened to take an entomology course and realized that it was possible to make a living playing with bugs! The rest is history.

What are your ultimate career goals?

I hope to pursue a career in research and/or extension that serves to find solutions to the threats of invasive arthropods to native ecosystems and agricultural commodities.

Research Interests?

I am interested in insects broadly, but more specifically I am passionate about integrated pest management.

What Interests You Most about Your Research?

I am amazed at the complexity of adelgid biology and natural history. The life strategies and evolutionary adaptations that make these minute organisms so successful are uniquely fascinating.

What are the Field Sites Like?

My research sites are located in beautiful natural areas, and spending time at them is, most of the time, as peaceful and reinvigorating as a recreational hike on a remote trail. However, since my sampling took place year-round, there were times it was less pleasant to be out there. Once I decided I needed to get out for my regularly scheduled sampling, and, against better judgment, drove out into the woods by myself on a solid layer of icy snow. I ended up getting our state vehicle stranded on a snowy bank and had to walk 3 miles out to the paved road and hitchhike the rest of the way to the only gas station for miles. After much effort, and with almost no phone signal, I coordinated a tow truck to pull the state vehicle out. That was a long day.

Favorite Thing to Do in Blacksburg?

By far my favorite thing to do in Blacksburg is to ride to Pandapas Pond and explore the Poverty Creek Trail System on horseback.

Article by Paul Wasel, written while taking ENGL 4824: Science Writing in Spring 2017 as part of a collaboration with Fralin and the Department of English at Virginia Tech.