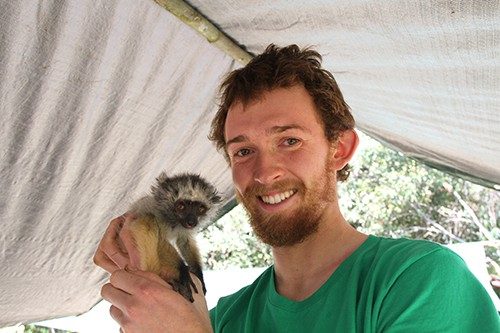

Brandon Semel

Flying high for conservation: an Interfaces of Global Change fellow will use drones to help save lemurs

Brandon Semel’s doctoral research can be traced back to a picture book.

Within the book are images of bushy tailed lemurs, hand drawn by an eight-year-old Brandon growing up in the Midwestern United States. He’d first seen the big-eyed primates on a wildlife documentary show on television and was hooked.

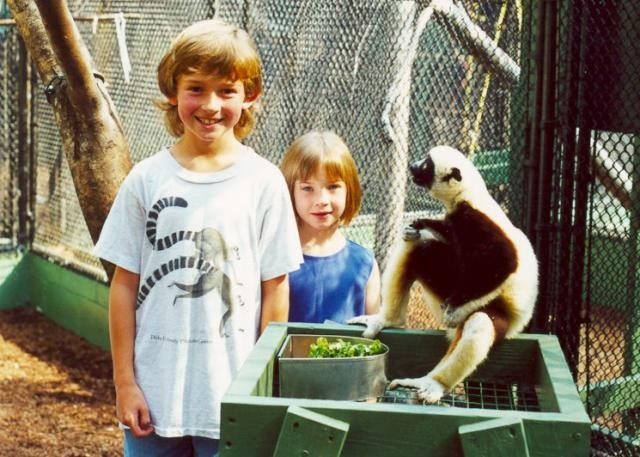

When Brandon presented his dad with the book, Brad Semel knew he had to encourage his son’s passion. He called the Duke Lemur Center and arranged a guided tour. They graciously obliged.

Little did Brandon know that the person who led the tour would one day be the advisor for his undergraduate research into the wild world of lemurs.

“I was told that a family with a third grader who knew a lot about primates, and lemurs in particular, had scheduled a visit,” said Dr. Ken Glander, a professor in the Evolutionary Anthropology Department at Duke University, and former director of the Lemur Center. “I was intrigued and told my staff that I was willing to be their guide on their visit. Brandon was unusual in that he was already much better informed than most young students; he was already at the level of many Duke undergraduates.”

Back home in Illinois, Brandon volunteered with the state’s department of natural resources, where he participated in wetland bird surveys, habitat restoration, and prescribed burns to maintain native prairies. While his knowledge and interest in all wildlife grew, he still had a favorite.

A love for lemurs

Rustling about in the slowly dwindling forests of Madagascar are all of the world’s lemur species—the blue-eyed black, aye-aye, fat-tailed dwarf, red-bellied, eastern woolly, white-footed sportive, greater bamboo, ring-tailed, and golden-crowned sifaka, to name just a few.

Madagascar, the fourth largest island in the world, broke off from the Indian sub-continent around 88 million years ago, leaving species to evolve in isolation. It is the only place in the world where lemurs, and many other unique plant and animal species, can be found in the wild.

Scientists think that lemurs were washed towards Madagascar from mainland Africa 55 million years ago by ocean currents, carried on mats made of vegetation. Some lemurs can hibernate—an ability that likely helped their ancestors survive the long journey. Other lemurs, like their ancestors, are nocturnal tree-dwellers; perhaps their shadowy nighttime presence is what earned them the name “lemur,” which comes from the word “lemures”—a ghost or spirit in Roman mythology.

These tree-dwellers come in a variety of shapes and sizes, ranging from the one-ounce mouse lemur to the 20-pound sifaka. Species today are just a fraction of the size of the earliest lemurs that lived in Madagascar prior to human settlement. All known extinct lemurs were larger than their modern relatives, with one the size of a female gorilla. Larger species had a hard time adapting to Madagascar’s changing climate a few thousand years ago, and were easy prey for Madagascar’s first human inhabitants.

Lemurs may be solitary, live in pairs, or be part of a group up to 20 members strong. Each group is ruled by a dominant female who has first choice of mates and food, which is usually plants or insects. Lemurs have long life spans for their size. Some live 16-20 years in the wild but can live for more than 30 years in captivity. Lemur reproduction is slow; females only ovulate for a few days during the year, usually between January and June. If impregnated, they typically give birth to one lemur at a time, or, on rare occasions, twins.

Of the 107 currently recognized lemur species, 24 were listed as critically endangered in 2013 by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This number is steadily growing due to human encroachment, deforestation, subsistence hunting, and climate change. In fact, the IUCN has named lemurs as the world’s most endangered mammals.

“Humans are the biggest threat to lemurs, and the human population in Madagascar is growing fast,” said Brandon.

The first time Brandon visited Madagascar was in high school on a family vacation. Staying in relatively nice tourist lodges near main parks and forests, the Semel family visited prime lemur and bird watching sites, learning about the wildlife from professional guides or translators who had a good deal of experience interacting with foreigners.

While the Semels got a bird’s eye view of the country, when Brandon would return a few years later as an undergraduate researcher, he’d see a whole different Madagascar.

A budding anthropologist

Come college time, Brandon knew exactly where he wanted to go. He chose to enroll as an evolutionary anthropology major at Duke University in order to gain the knowledge he needed to help conserve his beloved lemurs.

At first glance, anthropology seems like an odd choice, as the field is often centered on the study of humans. However, the close genetic tie between humans and other primates, such as lemurs, makes it the major of choice for primate researchers.

“Studying the wide diversity of social behavior, nutrition, culture, habitat use, and evolutionary history of primates, our closest living ancestors, can teach us a lot about early human evolution,” said Brandon. “Thus, primatology is often included under physical anthropology. Most people who study primates in the United States —whether they’re studying behavior, conservation, evolution, morphology, etc.— work out of anthropology departments.”

As an undergraduate researcher in the evolutionary anthropology department at Duke, Brandon began working as a research assistant to Dr. Luke Dollar, associate professor of biology, who had strong ties to the Duke Lemur Center.

With Dollar, Semel traveled back to Madagascar to investigate the effects of human encroachment on the fossa, the most significant predator to lemurs besides humans. Fossas—which made a Disney debut in the film Madagascar—resemble miniature mountain lions, though they are more closely related to mongooses.

By conducting extensive vertebrate surveys and trappings, the team that Semel worked with found that increasing feral dog populations were reducing populations of birds, reptiles, and mammals across the landscape. They also found that feral dogs were able to out-compete fossas for food. Therefore, the fossas were driven away from forest edges and deeper into the shrinking interior.

Living amongst native people while on research projects, Brandon saw a whole new Madagascar.

“Once I started to get a handle on the language, things really changed because I was no longer hearing second hand accounts of the challenges that people were facing,” Semel said. “They suddenly became real. People had individual hopes and dreams that I could understand and relate to, but the lengths to which people had to go to achieve them was mind-boggling and the obstacles seemed insurmountable. Everyone always talks about the Malagasy (the ethnic group that makes up the population of Madagascar) being tied to their homelands and families, so I was shocked to hear what lengths people would travel to find jobs or work, not knowing when or if they would be able to return home.”

Brandon learned about the specific environmental and economic challenges faced by the Malagasy. For example, he learned that poor tropical soils make a lot of the country’s land unsuitable for agriculture.

“When people need farm land, really all they can do is cut down the trees and burn them, to release those nutrients back into the soil,” Brandon said. “If you do that on a small scale, every few years, it can be sustainable. But Madagascar has one of the fastest growing human populations in Africa, in the world really, and so it has just become unsustainable.”

He also learned that in the rainforest areas, where it’s hard to keep domesticated animals, lemurs are the only real source of meat that the Malagasy have access to, and, therefore, hunting is a major threat for many lemur species.

While an undergraduate researcher in Madagascar, Brandon connected with Dr. Sarah Karpanty, an associate professor of wildlife in the College of Natural Resources and Environment at Virginia Tech. Brandon chose to continue his studies at Northern Illinois University where he got a master’s degree in anthropology; however, he stayed in touch with Karpanty, and this connection would prove important down the road.

A commitment to conservation

For his master’s thesis back in his home state, Brandon chose to study why two lemur species that live in Madagascar’s eastern rainforests eat soil. He investigated several potential reasons: parasite removal from the gut, acid neutralization, diarrhea prevention, that the soil packed enough minerals to serve as a daily vitamin, and that the dirt flushed out toxins in the system.

The toxins, Brandon found, come from the lemur’s diet, which consists of leaves and seeds packed full of toxins created by the plants for defense. In the end, he found that this was the most likely reason for soil consumption.

Brandon enjoyed his master’s research, but when he decided to go for a doctorate, he knew that he wanted it to be in a field in which his research would go beyond behavioral studies of lemurs to applied conservation research.

That’s what brought him to Virginia Tech to work with Karpanty. After applying for and receiving a National Science Foundation graduate research fellowship to fund his studies, Brandon came to Virginia Tech in August 2015. Now, he is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation in the College of Natural Resources and Environment, and a fellow in the Interfaces of Global Change interdisciplinary graduate education program.

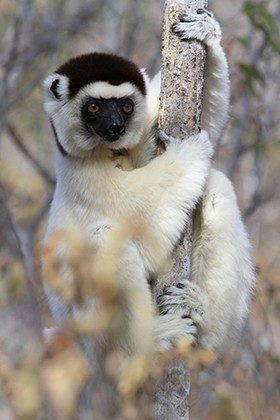

At Virginia Tech, he hopes to expand his lemur research by studying how climate change has and will continue to shape the distributions of critically endangered golden-crowned sifakas in northern Madagascar.

“Their habitats are highly fragmented,” Brandon said. “The entire species is found in an area half the size of Montgomery County. There are fewer lemurs than there are students at Virginia Tech.”

This summer, with the help of a $3,000 grant from the Cleveland Metro Parks Zoo, Brandon plans to use drone surveys to get the best data on population estimates of the golden-crowned sifaka in the forests of northern Madagascar. Drones are ideal for monitoring places that are hard-to-reach by foot, places where lemurs typically like to hang out.

The drone footage involves both still and moving photography, and geo-reference technology allows researchers to know the exact GPS coordinates where a lemur is photographed.

The use of drones for conservation research has become popular in the last few years. Ecologist Lian Pin Koh of Yale University founded ConservationDrones.org in 2012—an organization that seeks to raise public awareness about the use of drones for conservation purposes and to provide materials for researchers wanting to explore the technology, according to the group’s website.

While there are many regulations surrounding the use of drones to protect both people and wildlife, if successful, the technology has a lot of data to offer researchers.

“At the very least, drones can provide updated land cover data that’s often hard to come by and very expensive for conservation work,” said Semel. “But with the rate that drone technology is advancing, the sky really is the limit!”

Posted March 1, 2016

By Lindsay Key

Q&A: Meet Brandon

Hometown:

McHenry, IL

Major/Year:

First year PhD Student

Fralin Advisor:

Dr. Sarah Karpanty

Other Degrees:

Anthropology (M.A.), Northern Illinois University

Evolutionary Anthropology (B.S.) & Environmental Science (B.S.), Duke University

Why do you want to be a scientist? When did you know?

I view scientists as problem solvers. These problems could be at many levels, from those of global significance (how will climate change affect global food production?) to those of personal concern (how far can I push the expiration dates on the food in my refrigerator?). I want to be a scientist because I want to ask questions to which no one has the answer – and then go find it. I think the accompanying article makes it pretty clear when I started to discover that that was what I wanted to do!

What attracted you to your particular field of science?

Seeing new places and spending time outdoors are two of my favorite things. International conservation work is the perfect marriage between those passions. It also allows me to engage in work that future generations will (hopefully!) be able to appreciate and enjoy as the world around us continues to be transformed by industry and technology at such a rapid pace.

What are your ultimate career goals?

My ultimate career goal is to do something that doesn’t feel like work because I’m having so much fun doing it. Right now it’s a toss up between academia and working for a national or international non-profit aimed at protecting species and restoring their habitat.

Favorite hobby outside of school?

I love hiking, backpacking, and taking pictures along the way. This year is the centennial anniversary of our National Parks! I’ve managed to make it to one so far, but when Jefferson National Forest is so close, it’s hard to justify those long road trips.

Favorite thing to do in Blacksburg?

I really like going to performances at the Moss Arts Center. I think the inside of the theater itself is gorgeous. I could sit there and watch and stare at the empty stage all night if they’d let me!