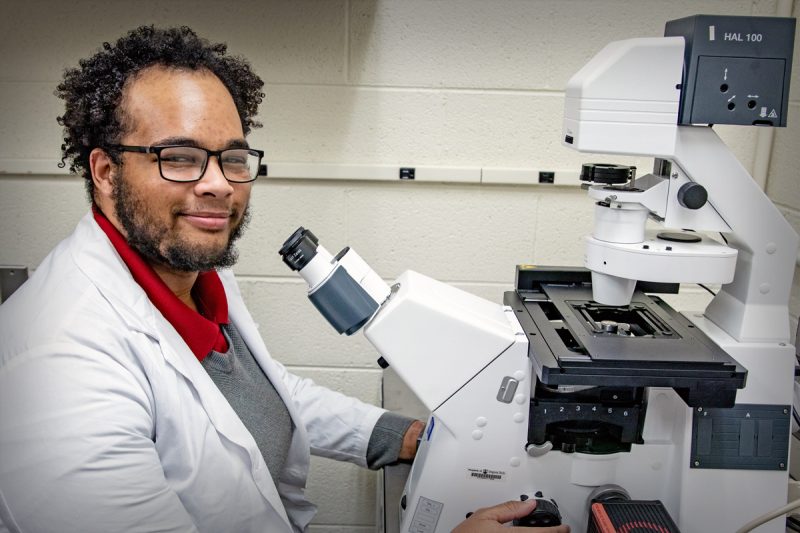

Aaron Brock

Ph.D. student studies spirochetal growth and implications for medicine

Bacteria may be hailed as one of the earliest forms of life and among the simplest of all organisms, but for graduate student Aaron Brock, bacteria are anything but simple.

“I love bacteria. They’re these amazing microorganisms that pretty much run the whole world. It really opens your eyes to what they’re able to do. What I want to do with my life is understand how these bacteria interact with their environment and what that means,” said Brock.

After graduating in 2018 with a bachelor’s degree in microbiology from Virginia Tech, Brock decided to continue his education in Blacksburg. He joined Brandon Jutras’s lab to study Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium responsible for causing Lyme disease, using molecular biology and microscopy techniques.

Specifically, Brock studies spirochetes, a phylum of bacteria well-known for causing prevalent diseases such as Lyme disease, syphilis, and leptospirosis. Despite the threats they pose, spirochetes are under-studied.

“One question I would love to solve before I graduate would be: How do spirochetes grow? They represent this unique phylum of bacterium that we don’t understand, so understanding how they grow would be a great question that I would love to solve by the end of my thesis. On its face, it seems like a very simple question, but it is extremely complex,” Brock said.

Bacteria synthesize a cellular component called peptidoglycan, an essential component of cell walls. This usually occurs through local or semi-lateral synthesis. But B. burgdorferi produces peptidoglycan both ways—in fact, it also has three sites of local synthesis. This deviation has stumped scientists, as they still don't know how the bacteria is regulating peptidoglycan synthesis.

“In general, what I’m doing is taking the common proteins that we know regulate growth and division in almost all life, especially in bacteria and plants, and seeing how they work in this unique system that we’re seeing with three zones of growth as well as ubiquitous growth and how that coordinates with other proteins,” Brock said.

Brock accomplishes this through microscopy, molecular genetics, and fluorescent probes, which allow him to tag proteins and see how they act. By understanding how the proteins involved with peptidoglycan behave, Brock hopes that his work will have applications in medicine.

“Medically, we just treat the bacteria with antibiotics that are very toxic to the whole human body. If we can better understand how to target certain proteins, such as proteins essential for growth, then we can find better therapeutics for patients. If the bacteria can’t grow, they can’t cause disease,” Brock said.

Brock’s fascination with bacteria dates back to when he was a child visiting the hospital where his mom worked as a pediatric nurse.

“I was that annoying kid that always asked endless questions, and she was the ever-so-gracious mother that answered all of them. It always got into this cycle of how people got sick, and how they got sick, and she would eventually tell me about bacteria. I got to a point where she didn’t know the answers to my questions anymore, and being the curious person that I am, I wanted to answer those questions for myself. Understanding what bacteria do in their environment first started with: Why bacteria do what they do inside of a human?” Brock said.

He carried his curiosity about bacteria through his college career and pursued opportunities to study them. He first started undergraduate research at Piedmont Virginia Community College, where he studied plant-toxin interactions under Joanna Vondrasek. When he decided to transfer to Virginia Tech, Vondrasek connected him with Birgit Scharf, a professor of biological sciences in the Department of Biological Sciences in the College of Science and an affiliated faculty member of the Fralin Life Sciences Institute. In the Scharf Lab, Brock continued undergraduate research on plant-microbe interactions

“I was working directly under Dr. Scharf, and I was running my own little side experiments. I did all of my own experimental planning and figuring out my own problems, which is a direct correlation to grad school. I am applying every skill I learned in her lab, even though I’m now doing a completely different project,” Brock said. “I would suggest undergraduate research to everyone, specifically for people in STEM, but everyone in general. In any department, there’s always research to be done. It really gives you real-world experience.”

Now, it is Brock’s turn to mentor undergraduates. In the Jutras Lab, he encourages his mentees to become independent thinkers, learn to ask questions, and discover their own answers. Thankful for the mentors he’s had, Brock hopes to offer that same mentorship to a budding scientist.

“Aaron is a fantastic addition to the lab. He is quick to provide assistance and support to anyone in need. If the lab was a car, Aaron is the engine,” said Brandon Jutras, assistant professor in the Department of Biochemistry in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Additionally, Brock entered graduate school through the interdisciplinary Molecular and Cellular Biology Graduate Program at Virginia Tech and joined the biochemistry department. The interdisciplinary program connects departments from across campus to create an inclusive environment that encourages scientific curiosity, ethical conduct, independent thinking, and community engagement. MCB is comprised of affiliated faculty from six departments as well as their students. The program offers get-togethers to talk about graduate life, research, and current events, which Brock says creates an important community of support.

“As a graduate student, I have my department, the grad school, and MCB as an interdisciplinary program, so I am connected to all the departments that we’re associated with. I already had this great relationship with Virginia Tech, but now it’s become so much better because of MCB,” Brock said.

Brock’s endless curiosity about bacteria has propelled his research through the years, but he says he’ll never be done asking questions of “how” and “why.”

“In the long term, I know that, at the very least, I want to continue in research. Questions of how and why will never be answered for me because there will always be another how and another why. I will always be in research—I haven’t decided if that will be in academia, industry, or government, but all I know is that I will continue in research.”

— Written by Rasha Aridi