Xiaoyan Sheng

Sleeping trees and a Virginia Tech guardian who nurtures them

It’s a cold, dry December day in Blacksburg. Outside, between Fralin and Latham Halls, the trees are mostly bare, though some still have a few limp leaves.

Inside Latham is a warm, brightly lit room with rows of tree specimens. They range in size from tiny seedlings to quarter-size buds and are stored in round clear dishes. Some have sprouted into short plants, two to four inches high.

“Here you can see a sleeping tree and a growing tree,” says Xiaoyan Sheng, a plant geneticist at Virginia Tech, as she holds two transparent containers side by side.

In the spring and summer, trees enjoy the long days of sunlight and steady rainfall. They grow and extend their branches with new growth, or shoots, so leaves can grow.

But as seasons change, days shorten and air gets drier. As fall turns to winter, trees use decreased day length and cooler temperatures as cues to slow growth and develop dormancy – a process in which trees stop growing and make metabolic changes to protect against winter’s freezing temperatures. When this happens, they look dead, as their leaves have fallen and their spiny branches are crooked and naked.

“They get sleepy,” says Sheng, who manages the Forest Genomics Lab at Virginia Tech while working on a Ph.D. in forest resources and environmental conservation in the College of Natural Resources and Environment.

With ten years behind in her in the lab, Sheng loves the details. She’s particularly interested in the genetics behind how trees go to sleep and wake up – or transition from fall to winter, then from winter to spring.

“I’m really excited most of the time, because I’m a molecular and biotech person. I really like seeing how genes are useful for studying the trees.”

Sheng’s main focus is to identify the genes responsible for seasonal transition in poplar trees, commonly known as cottonwoods or aspens. These are broadleaf trees, also known as deciduous, meaning ‘falling off,’ for the autumn behavior of their leaves. These trees also tend to grow flowers right before they grow new branches. A particular gene, the flowering time or FT2 gene, controls this behavior.

“Poplar trees have this flower time gene, but in these species, this gene controls multiple things in addition to the flowering,” said Sheng.

When this FT gene is turned on, trees resume growth as they would in spring. When the gene is turned off, the tree stops growing and becomes dormant.

But, how and when is this gene turned on, and to what extent does climate variation alter when it’s triggered?

Working with principal investigator Amy Brunner, an associate professor of molecular genetics, Sheng experiments with the genome of the poplar species to find out. Using a new gene-editing biotechnology tool, she designs gene-specific targets to alter the FT gene of the species before they grow specimens to study in the lab.

“About two years ago,” she said, “I became really excited when I discovered the new gene editing tool, the CRISPR-Cas9 system. I met another professor who was using it to modify plants, so I worked with him so we could start using it in our lab.”

With the help of hardworking undergraduates, she and the team are able to isolate the tree’s DNA sequence to locate the gene. Then, Sheng uses the gene-editing tool to delete or insert nucleotides that code for amino acids, which ultimately help the tree know when to rest.

“It’s rare to find someone who is such a skilled molecular biologist, excited about the science, and also undaunted by the large amount of plant tissue culture that is needed to have a continually active poplar transformation pipeline,” said Brunner, who leads the research team, which is the only group on campus specializing in poplar tree genomics.

Together, the lab team is then able to see what else happens to the trees on the genomic level, and how this corresponds to what they find in the growth chamber.

“This gene is sensitive to different environments, like drought. But trees are really smart. If they don’t have enough water, then they will stop growing and fall asleep,” Sheng said.

This means they look wilted or droopy.

“Studying environmental conditions and how they affect the plant are new, and we’re seeing new ways conditions affect the genes. We want to explain how trees respond to different environments, especially for tree breeding. We know certain locations always have drought conditions, so we want to make species that can grow and survive.”

Nurturing young buds

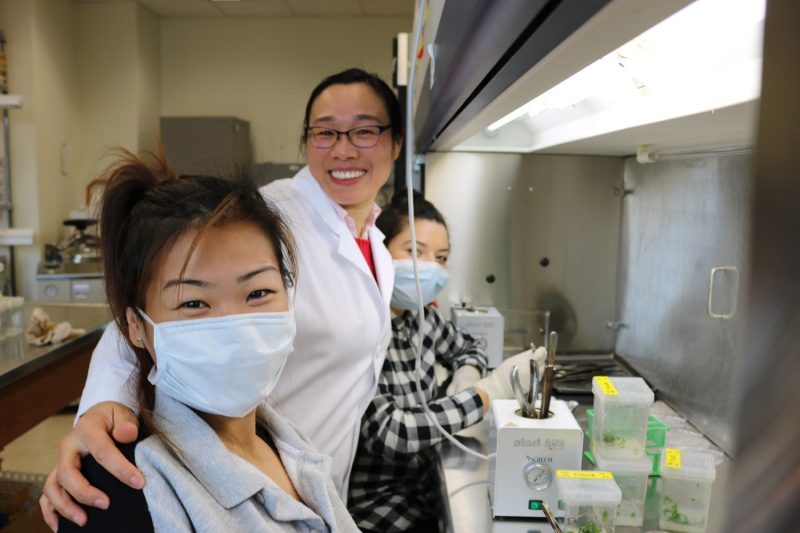

Though working with sleepy trees is a major role for Sheng, she also manages the lab’s data, stocks its supplies, and mentors undergraduates, including designing experiments and analyzing the data. She usually has 4-6 undergraduates at any given time.

Back in the lab, sitting in front of her computer, she turns and smiles so big her eyes shut. “I love them,” she says. “They are so eager to learn because it’s completely new to most of them. Usually they’ve heard about something in biology class, but they don’t know what it is. So, I show them how to get the tissue, how to get the DNA, and then they are really excited.”

Still smiling, she jumped a little, her face turning red with excitement. “And then when they get it, you hear them say, ‘Oh! I did it!’”

She remembers almost all of her students by name, and finds her work with them extremely important.

So important, in fact, that she recalled Joseph Edwards, a former Virginia Tech undergraduate.

When Sheng met Joe, he was majoring in forestry. But, he didn’t really like it, she recalls, so he switched to biology.

“He was worried because he didn’t have a biology background, so he read a lot and learned skills from the lab, including working over the summer as an undergrad. He then went on to graduate school.”

Last year, he came back to visit. “He told me that working with me saved him about a year of his Ph.D. work because he knew what to do.” She beamed as she talked. “I was so glad because he was really a great student.”

“Xiaoyan took me under her wing when I started in the Brunner Lab as an undergraduate,” said Edwards, who finished his doctorate this month in plant biology at the University of California at Davis. “I had no practical lab experience nor had I even a rudimentary knowledge of molecular biology. I had just switched my major to biology on a whim, so the last thing I was expecting was to have her ask my opinion about planning experiments or interpreting results. But that’s what she did. This was so important to me, as planning and strategy are really the nuts and bolts of science. Throughout my time in graduate school, I have been lucky to mentor undergraduates of my own and I model my mentorship of undergraduates after Xiaoyan’s mentorship of me.”

Laughing, she recalled that when he visited, she was sick with the flu. “I said, ‘I’m sorry, I’m sick!’ and he said, ‘Hug me, I’m not afraid of you!’”

“When Xiaoyan first started, training students was new to her, but she grew to like it and excel at it. To really benefit from this type of research, undergraduates need someone who spends most of the day in the lab with them. Because of her dedication, we’ve been able to host more than 40 students, with most working in the lab for multiple semesters. That longer time frame makes a huge difference in the quality and depth of the undergraduate research experience,” Brunner said.

This year, while many of her current and former students are traveling over the winter break, Sheng will stay close to campus to keep an eye on the plants in the growth chamber.

“I never expect to hear from them,” she confided, “but it’s so rewarding when they come back and visit.”

Posted December 20, 2016 by Cassandra Hockman

Q&A: Meet Xiaoyan

Hometown: Guangxi, China

Academic Degrees:

Bachelor of Science, University of Guangxi

Master of Science, University of Hunan Agriculture

Master of Science, University of Saskatchewan

Fralin Lab: Amy Brunner

How did you get interested in plant genetics?

I grew up on a small farm in China where my parents grew rice. So, I always wondered how could we grow plants for higher yield and for good taste. When I would play in them, I wondered how they grew.

Since then, I have always considered myself a plant person. I worked in the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Beijing, China, and I got a Master’s in plant breeding and genetics.

For our research, we would grow plants in the field. We then would choose the best two plants as a mother and a father, and cross them to produce seeds of second, third, fourth generations and so on. We didn’t know the genes inside the plant, just the plants in the field. But we could watch for higher yield or more disease resistance.

Then, you get the plants growing and you would just look at the plant and see what they looked like. And then you’d just assume the genes were connected. At this point, the technology wasn’t there to study and look at the genes themselves. So, most of the time we would just see what the new plants looked like.

How, then, did you get interested in biotechnology and gene editing?

Two decades ago, gene sequencing and cloning was more advanced in the U.S. than in China, so I moved to Canada to learn and use this new kind of technology. I was at a conference in China when I learned about the gene. I met a professor who told me a gene was a piece of DNA sequence, but I didn’t have any idea. So, he told me about an institute in Canada who had the ability to actually look at the DNA sequence.

"Wow," I said. This really changed my world.

And so, I got interested and decided to move to Canada because this kind of technology was there.

What does managing a lab look like for you?

I manage multiple research projects all the time, where I mainly make transgenic plants. Half my time is also spent with students to guide them as they make transgenic plants, but they are also learning a lot of high tech skills, so I mainly guide them and bring them all together.

Most of our students work in the lab, though they don’t know how to design experiments. So I work with them to design experiments since they aren’t as familiar with the details. I also summarize and analyze their data to see what’s going on.

Then, I also do a lot of troubleshooting. This includes referencing other scientific papers. Sometimes you have to borrow and optimize conditions from other experiments because science always comes with a problem, so I have to change things to see what works for us.

What do you like most about Virginia Tech?

Closeness of the Hokie community. No matter where you go on campus, classrooms, labs, offices, and libraries, you always see friendly students, faculty and staff around.

What do you think are some of the most important skills for undergraduates to learn before graduate school?

Most students can learn many technical skills in a short period of time. Soon after they learn enough basic experimental skills, I encourage students to take charge of specific projects and complete the projects with minimal supervision. In this way, they can learn comprehensive skills from applying technical skills, planning and designing experiments to independently thinking of scientific projects, as well as good time management.